Dead Voltage: Virginia’s House of Execution

- aelectricstars

- Dec 27, 2025

- 6 min read

In Virginia, death didn’t come quietly.

It came bolted to the floor, humming behind thick walls, waiting its turn.

The electric chair arrived in the Commonwealth in 1908, sold to the public as progress—cleaner than the rope, more modern than the drop. The state traded gallows for wires and called it civilization. From that moment on, Virginia’s executions moved indoors, away from town squares and into locked rooms where only a handful of witnesses would ever see what really happened.

For most of the 20th century, the chair lived inside the Virginia State Penitentiary—a hulking brick fortress in Richmond that became synonymous with punishment. Men passed through its gates knowing the odds. Once your case funneled all the way down to that chair, the state rarely blinked.

By the time the penitentiary closed in 1991, hundreds had been executed there. The chair had done its work long enough to earn a reputation—not just as a method, but as a presence. Guards talked about it like a thing that listened. Inmates spoke its name like a curse.

When the old prison was torn down, the chair didn’t disappear. It was moved—rebuilt inside the newer Greensville Correctional Center. Same purpose. Cleaner walls. Same end.

The people who met it

Virginia didn’t market executions as spectacle, but some names burned through the silence anyway.

There was Virginia Christian, one of the few women ever electrocuted by the state—young, poor, and swept up early in the chair’s history when mercy was scarce and appeals were thinner than paper.

She was young—barely into adulthood—poor, Black, and living in a Virginia that had already decided what someone like her was worth. In 1912, the electric chair was still new enough to be called progress, but old enough to be used without hesitation. Mercy was a word people liked to say. Appeals were thinner than paper. And Virginia Christian had neither.

She had worked as a domestic servant. When an argument with her white employer ended in violence, the state moved fast—faster than it ever moved for mercy. There was no drawn-out legal saga, no years of appeals, no national campaign pleading for restraint. The gears of justice turned briskly when the condemned was poor and female and expendable.

The trial came and went. The sentence followed. Death.

By the time Virginia Christian arrived at the Virginia State Penitentiary in Richmond, the chair was already waiting—wood polished, leather straps conditioned, wires tested. She was small in it. That detail mattered to witnesses later. People remembered how young she looked. How slight. How badly she fit the story Virginia wanted to tell itself about who deserved to die.

On the day of her execution, there was no sense of spectacle—only grim purpose. Guards did not shout. Officials did not waver. The state had already rehearsed this outcome in its head and was eager to see it through.

She was led into the chamber, the weight of the room pressing down on her before the straps ever did. Leather closed around her limbs, firm and final. The chair did not care that she was a woman. The chair did not care that she was young. It had been built for bodies, not biographies.

Witnesses later described the moment as uncomfortable in a way no one wanted to linger on. The electric chair had been advertised as efficient, humane—yet watching a young woman secured into it made those words feel thin, performative.

When the hood came down, it erased her face from history in real time. Whatever fear she felt, whatever thoughts raced through her mind, they vanished behind cloth and protocol. The state preferred its executions faceless.

When the current was applied, the room stiffened. The body reacted in ways that shocked even those who believed in the process. This was still early in the chair’s history, when the promise of clean efficiency had not yet been fully interrogated by reality. What witnesses saw lingered with them—not because it was chaotic, but because it was so final.

Minutes later, it was over.

Virginia Christian was pronounced dead, her life concluded by a machine barely older than she was. The witnesses left. The paperwork was signed. The prison returned to routine.

Outside the walls, the world moved on.

For Virginia, there would be no appeals written about in law journals. No posthumous reconsideration. No long debate about whether the state had acted too quickly or too harshly. She became a footnote—one of the few women electrocuted by Virginia—her youth and poverty folded neatly into the justification.

She was swept up at the beginning of the electric chair’s reign, when the Commonwealth was eager to prove it could kill efficiently, decisively, and without doubt. And she proved something else instead: that when mercy is optional, it is usually withheld from those who need it most.

Virginia Christian did not just die in the chair.She was absorbed by it—turned into precedent, proof, and silence.

Decades later came Roger Keith Coleman, whose final words—“An innocent man is going to be executed”—echoed far beyond the chamber. His case became shorthand for everything terrifying about finality: once the switch is thrown, doubt doesn’t matter anymore.

There were others. Fewer remembered by name. Most reduced to case numbers, docket entries, and death warrants stamped and filed away.

How Virginia delivered someone to the chair

The process was slow. That was the point.

First came the trial—capital murder, special circumstances, a jury asked to decide not just guilt but whether someone deserved to keep breathing.

Then the appeals. State courts. Federal courts. Years stacked on years. Lawyers filing motions while the condemned aged in a cell designed for waiting.

Finally, when nothing else was left to argue, the Governor was asked for clemency. Almost always, the answer was no.

That’s when the date arrived.

Your last day

You are scheduled to die in Virginia.

Not in theory. Not someday. Tonight.

Before the clock reaches nine, they move you. The walk is short, but it doesn’t feel that way. You’re taken into the execution chamber at Greensville Correctional Center, where the air feels heavier than the rest of the prison—like the room itself knows what it’s for.

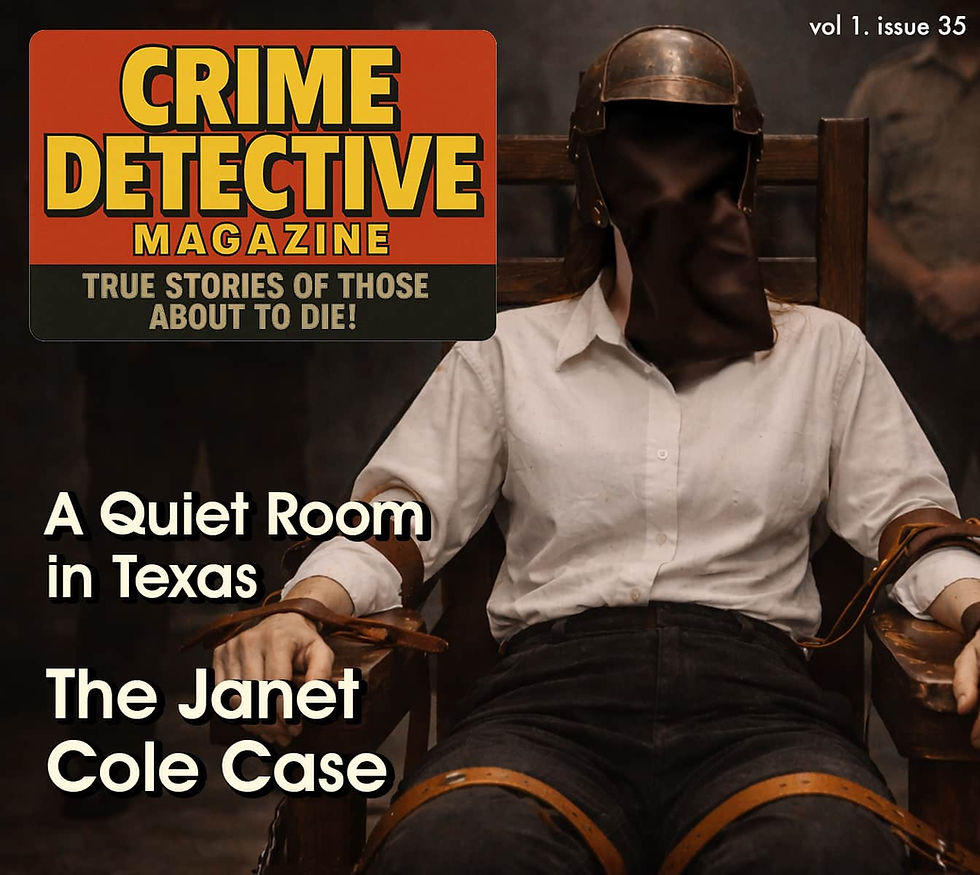

The chair is already waiting.

They don’t ease you into it. They don’t have to. You sit where they tell you to sit. Leather straps are pulled tight across your arms, your legs, your chest. Each one is checked, then checked again. The goal isn’t cruelty—it’s certainty.

Your head is forced back against the wood. A leather restraint is secured, holding your skull in place so you can’t turn away. A mask follows. It presses close, leaving just enough space for your nose. Enough room for breathing. Not enough for comfort.

Then the helmet comes down.

It’s heavy. Leather. Two halves that close around your head like a shell. Buckled tight beneath your chin. Once it’s secured, there’s no room to move—not even to nod. The world narrows to darkness, pressure, and the sound of your own breathing echoing inside the mask.

A cuff is fastened to your leg. Another point of contact. Another reminder that your body now belongs to the process.

Everything happens fast now. Faster than you expected. Faster than you can emotionally catch up to. Hands move with practiced efficiency. No one speaks to you anymore.

Behind the chair, someone turns a key.

You hear it.

That sound—the small, ordinary click—means there’s no turning back. It’s the quietest sound in the room, and somehow the loudest.

A moment later, the signal is given.

Your body reacts before your mind does. You slam back against the restraints as power surges through you, muscles locking, jaw clenching so hard you think it might break. You’re no longer in control of anything—not breath, not movement, not pain.

There is a pause. Brief. Not relief—just suspension.

Then it happens again.

The second wave hits harder because your body already knows what’s coming. You’re held there, trapped in the chair, the current doing what it was designed to do. There’s no screaming. There’s no thrashing. Just tension, pressure, and the overwhelming sense of being overwritten by the state.

When it’s finished, the room doesn’t rush forward.

They wait.

A medical authority steps in. Checks for signs of life. Waits. Checks again. The official time is noted. Everything is logged down to the second—when it began, when it ended, when you were pronounced dead.

Several minutes later, it’s made official.

Death, confirmed.

The curtain closes. Witnesses are escorted out, some shaken, some silent, some already rewriting the experience in their heads so they can live with it. Guards return to routine. The chamber is reset.

Paperwork follows.

Times recorded. Signatures added. A final line drawn beneath your name.

Another execution completed.Another chair emptied.Another night ending exactly the way Virginia planned it.

The end of the chair

By the 1990s, the country had started to look too closely at what electrocution actually did. Virginia switched to lethal injection in 1994—quieter, cleaner, easier to defend in court. The chair was retired, but not forgotten.

In 2021, Virginia abolished the death penalty entirely. The Commonwealth that once executed more people than almost any other state stepped away from the practice altogether.

The chair didn’t get a ceremony. It never does.

It just stopped being needed.

And somewhere in storage, behind locked doors, it sits like it always did—silent, heavy, and waiting for a sentence that will never come again.